Training for Mountaineering 1

Q: Can’t you just climb more for training?

A: Well, yes and no. We would argue there is a better, more effective way!

Mountaineering is demanding, involved and very committing. It can place a huge amount of stress on our biological and biomechanical systems. If you are heading towards a mountaineering trip or expedition, or have a particular goal in mind, we think that specific, consistent training not only offers the best chance of success, but also increases your changes of staying injury free.

We’ve all heard the phrase “control the controllables.” In mountaineering, this can refer to many aspects, such as equipment, nutrition and advance planning. Our energy levels are also one of our major controllables. The ability to maintain energy levels, to keep going after a prolonged effort and to push fatigue and exhaustion further away could, literally, be a lifesaver.

Capacities vs Skills.

As coaches, when we are preparing an athlete for an ambitious goal we look at two main components: Capacities and Skills. In short, skills reflect an athletes ability to control your body effectively and to complete complex tasks efficiently. An Athletes capacities determine for how long the athlete can continue to perform the skills properly.

When training for a mountaineering goal, athletes should seek to develop both their Skills and Capacities. In this instance, skills could be described as including technical movement patterns when climbing, route reading ability, guidebook interpretation and ropework etc. Capacities can be described as including strength, fitness and cognitive abilities.

Skills are improved through long term practice and instruction.

At Blackthorn Strong, we specialise in improving an adventure athlete’s capacities (but we can recommend some excellent instructors for improving your skills if needed). There is, of course, overlap. We would suggest that one of the most crucial mountaineering skills is that of decision making. Clearly, the greater your capacities and the more you have “left in the tank” the better you will able to continue to make sensible and safe decisions.

Capacities

Under the Blackthorn Strong systems, we consider an adventure athlete’s capacities to be

Aerobic Fitness

This is the body’s ability to produce energy, using oxygen, efficiently.

Strength Training

The ability to express force.

Loading Capacity

The tolerances of bones, muscles and connective tissues to loading.

Muscle Endurance

The ability to sustain performance at a particular intensity.

Efficiency of Movement

An athlete’s efficiency at performing a skill.

These Capacities will be explained in detail in Part 2.

So, if we know what our capacities are as mountaineers, how do we go about improving these through training?

Principles of Training

The human body is amazing. It has the ability to adapt to new stresses and loads, and that is, effectively, how training works. If we start to try and left heavy things, our body will realise that’s what we want it to do, so will adapt (over time) to be better at it. The same goes for running, or cycling etc. This, in a broad sense, describes the “Stress Adaptation Theory of Training.”

General Adaptation Syndrome

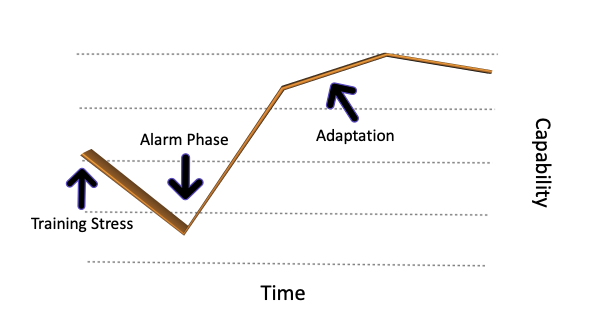

General Adaptation Syndrome, or GAS is the most dominant model used to described the training process:

Fig 1.1

Let’s say that a training session is the application of training stress. The purpose of training stress, or training stimulus is to prompt an adaptation.

Adaptation takes place after the training stress is applied (Fig1.1). Allowing adequate time for recovery is important.

The next training session should be scheduled to take place at the point of maximal adaptation, and not delayed until adaptation has began to decrease.

Fig 1.2

Repeated cycles of the stress-adaptation cycle can produce notable and significant improvements in performance (Fig 1.2).

Fig 1.3

Further to that is the idea off super-compensation. This theory suggests that if we were to time our training so that we train before we are fully recovered, then there will be a further decline in our capability. This is called over-reaching. But, if we we were to then allow enough recovery time, the resulting increase in capability will be larger, we will super-compensate (Fig1.3).

Progressive Overload

Progressive Overload may be the most crucial ground rule for training. It is an evolutionary result of GAS. The principle is well described by the story of the ancient greek wrestler, Milo and the Bull.

Milo of Croton taught us the three basic principles of building muscle. Public Domain

The story goes the Milo, as a young boy lifted a calf. He continued to lift the calf everyday, until it was a fully grown bull. As a result, his strength levels grew phenomenally and he became a renowned wrestler and strongman.

Because the weight of the bull kept increasing (creating new stimuli), Milo’s strength kept increasing. The stimuli (overload) became progressively larger.

Essentially, as we adapt to each new load, we require a new, heavier load to promote further adaptation.

A good training programme makes use of intensity, volume, frequency of training, type of training and recovery to encourage overload, rather than just increasing the weight lifted every time. Note that done wrong, or increasing the load too fast, can quickly lead to injury.

Specificity

When it comes to mountaineering, one size doesn’t fit all. This is where specificity plays a critical role. Your training must mirror the demands of the mountain. If your goal is to summit a technical alpine route, your training should focus on the physical and mental demands of that task — steep climbing, high-altitude endurance, and precise, skilled movement.

General fitness is important, but specificity is key to building the precise capacities that will allow you to handle the unique stresses of mountaineering. Strength, endurance, and cardiovascular fitness all need to be developed with the specific challenges of your objective in mind. Think about the terrain, the length of the route, the conditions you’ll face, and even the altitude. A training plan that is too generic may not push you to the level required for your specific challenge.

For instance, you don’t need to train like a marathon runner if your expedition will involve high-intensity efforts in short bursts, interspersed with long, grueling uphill hikes. Training with specificity means targeting those key movement patterns and energy systems that you will use on the mountain, so you are as prepared as possible when the time comes.

Individuality

No two mountaineers are the same. The principles of training should be adapted to each individual’s strengths, weaknesses, and goals. Whether you are climbing with a team or going solo, your training must take into account your current fitness level, injury history, skill set, and unique demands of the route you’re targeting.

This principle of individuality is often overlooked in traditional training programs. But it’s essential when preparing for mountaineering. One athlete might excel in aerobic conditioning but struggle with strength endurance. Another might have an impressive strength-to-weight ratio but lack the mental fortitude to sustain effort under extreme fatigue. A successful training program must cater to these differences by prioritizing specific capacities and skills.

Taking a personalized approach ensures that you’re not wasting time on exercises that don’t serve your needs, and you’re not neglecting areas that require more attention. Tailoring your plan means training smarter, not harder, and maximizing the effectiveness of each session.

Reversibility

Training adaptations are not permanent. When you stop training or reduce the intensity and volume of your exercise, your body will begin to lose the gains it has made. This is the principle of reversibility.

Mountaineering requires a high level of physical conditioning, and if you back off from your training for an extended period — whether due to injury, a busy schedule, or post-expedition recovery — you will begin to lose strength, endurance, and efficiency. Your capacity to handle extended physical effort will diminish, and those key movement patterns you’ve worked on will deteriorate.

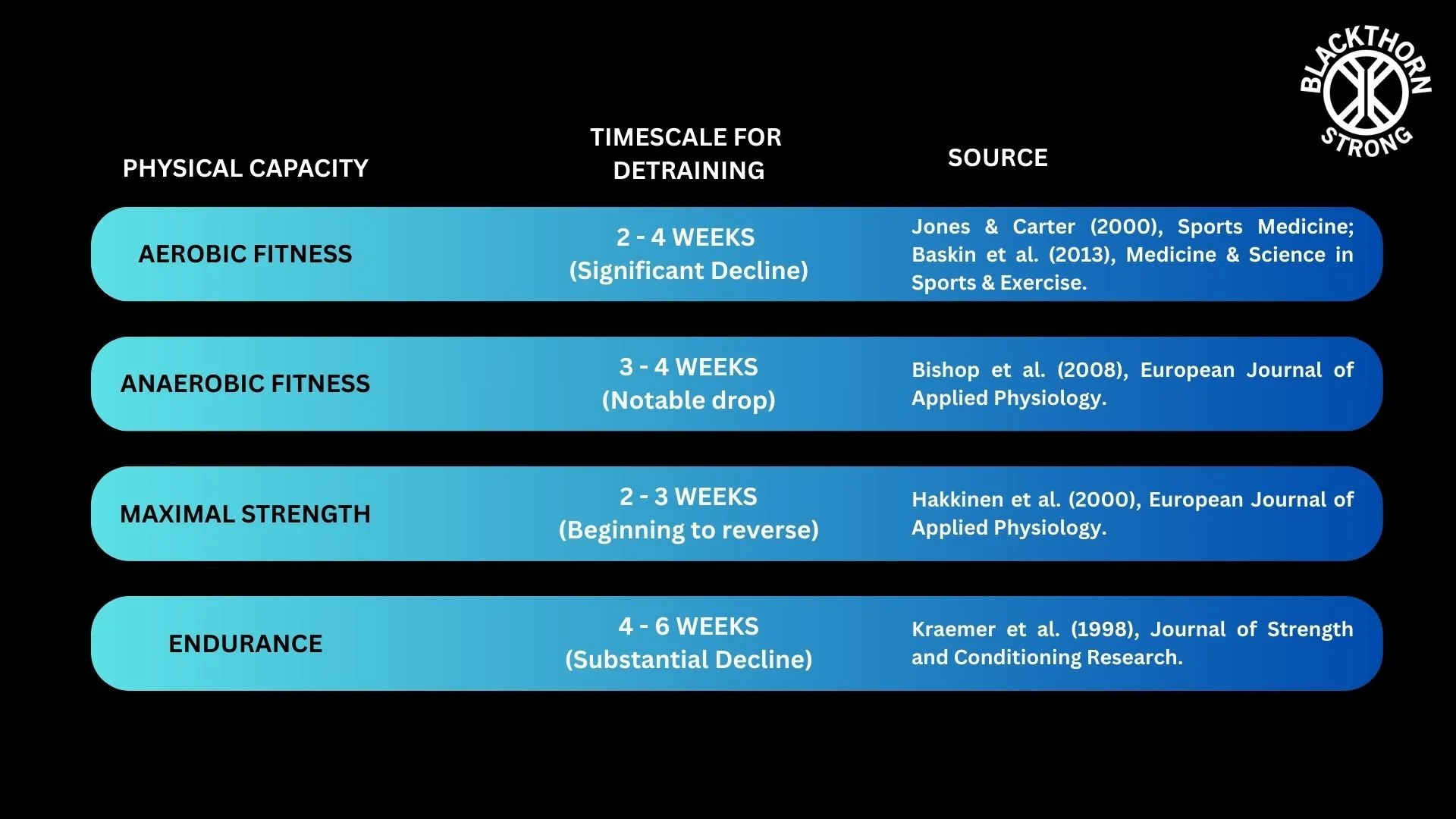

To give you an idea of how quickly various components of fitness can be lost, here’s a table summarizing research-backed detraining timescales:

Aerobic Fitness (VO2 max):

Aerobic fitness begins to decline within a few days to weeks of reduced training, with notable reductions occurring within 2-4 weeks. The drop in VO2 max (a key measure of aerobic fitness) has been shown to be relatively rapid, with an average decline of about 8-14% over the first month of detraining. This is particularly important for mountaineers who rely on sustained aerobic capacity for long climbs or high-altitude endurance.

Sources: Jones & Carter (2000), Baskin et al. (2013).

Anaerobic Fitness (Lactate Threshold):

Anaerobic fitness, which involves the body’s ability to sustain high-intensity efforts, can show a decline within 3-4 weeks of detraining. This capacity is crucial for explosive movements, such as steep uphill sprints or technical climbs. The lactate threshold, a measure of intensity at which lactic acid builds up, decreases with a reduction in training.

Source: Bishop et al. (2008).

Maximal Strength:

Maximal strength declines within a 2-3 week period after training cessation. This can affect a mountaineer’s ability to perform heavy lifting, such as carrying a loaded pack or moving through challenging terrain that requires raw power. The loss of strength is typically slower than the loss of endurance, but it's still a critical factor for overall mountaineering performance.

Source: Hakkinen et al. (2000).

Endurance (Muscle Endurance):

Muscle endurance, which involves sustaining moderate efforts over time, begins to reverse significantly after 4-6 weeks of detraining. While maximal strength may decline slower, endurance is much more susceptible to reversibility. Mountaineers will feel this most when trying to sustain climbing efforts or long-distance hiking under fatigue.

Source: Kraemer et al. (1998).

Reversibility emphasizes the importance of maintaining a consistent level of training, especially when preparing for a mountaineering expedition. Even if you take a break from full intensity, it's crucial to keep a baseline level of fitness to prevent a significant loss of the gains you've worked hard to achieve. Regular, even low-level, activity can help mitigate the effects of detraining and keep you prepared for your next challenge.

So: consistent, specific and well-programmed training can reap significant rewards!

Watch here for part II, where we delve into detail!