How to Stay Motivated

Ok, hands up, that’s clickbait. The reality is that you simply cannot maintain high levels of motivation at all times. We get so many people talking about “I just need to find the motivation” “I can’t be bothered today” “Struggling to get motivated this week” and so on and so on.

Motivation, like most emotions has peaks and troughs. It tends to be high at the beginning of a programme or when a new goal is established or when progress is demonstrated, such as weight loss, strength gains or hitting that new grade. The pursuit or expectation of a state of feeling permanently motivated is as pointless as it would be to expect to be permanently happy or sad. Or satisfied.

Patterns get tired. As the patterns get tired, so does the motivation. People’s priorities shift, lives get busier and exercise goes from being a passion to an occasional partaking. Weight goes on, fitness wanes and it goes back to being a “someday, when I find the motivation…”

Patterns of engagement and disengagement is manifested in attendance and retention. At the beginning of a new programme, or with a new client, all training sessions are met and followed with gusto. Motivation is the fuel that keeps them coming but, as it dwindles, the previously easily-overcame barriers seem larger and attendance starts to slacken. Less attendance tends to mean less positive reinforcement, which leads to less attendance.

When it comes to programming for athletes and professionals (especially busy professionals), an understanding of behavioural science is almost as important as exercise science. This is why we spend a significant amount of time looking at, studying, and understanding human behaviour on The Adventure Professional programme.

The bottom line is that motivation is not enough. We need to build and maintain effective exercise behaviours. Often, the way to effective exercise behaviours is through better lifestyle behaviours, but we’ll leave that focus for another day.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Where do we start?

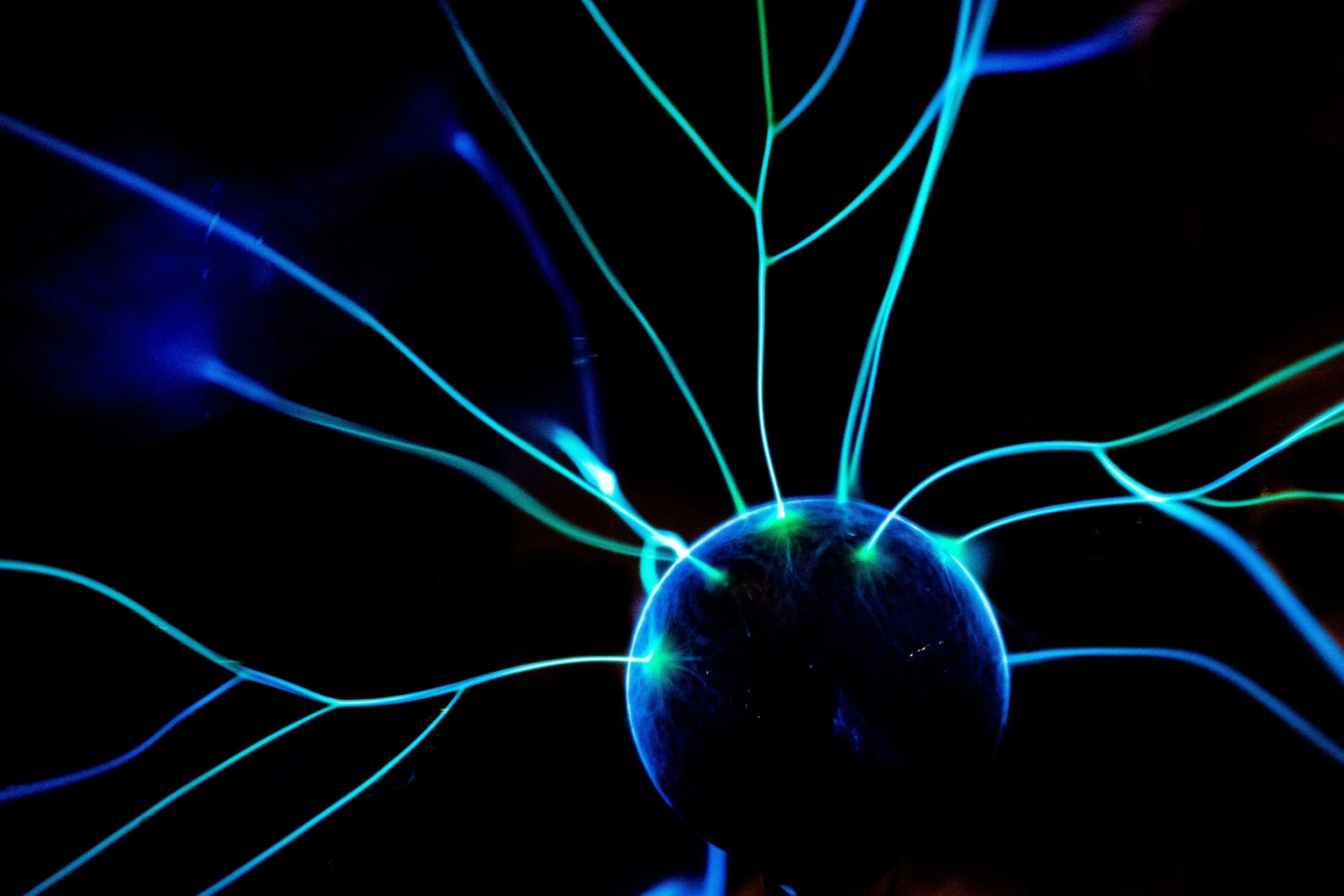

We start where the behaviour is formed. The squishy mush between your ears.

The brain demands 20% of your body’s energy use.

Has over 100 specialist chemicals (neurotransmitters) which pass information.

Is made up of around 86 billion neutrons and 86 billion glial cells, which support the neurons.

In short, the brain is inconceivably complicated. Our conscious thoughts take place, really, in the outer 2.5mm of the brain. Our subconscious takes place much deeper within. Every second of every day, our subconscious is receiving, filtering, assimilating and acting on a huge amount of information being taken in through our senses.

Simply, in order to create exercise behaviour, we need it to be in the subconscious. The subconscious works very efficiently, generally because the connections required have already been made. There is no need to expend loads of energy by learning or analysing. In this case, tasks that are already known and understood just need to be carried out with efficiency (like breathing).

So, establishing exercise behaviour requires conscious effort in the first instance. The planning, problem solving and implementation. But, control of the behaviour needs to be transferred to the subconscious. The conscious mind has too much else to do to reliably keep up with our new exercise behaviour on its own.

Essentially, we need to make it a habit.

How do we build it?

Habits are defined, within psychology, as “actions that are triggered automatically in response to contextual clues that have been associated with their performance.” A simple example of this is putting on a seatbelt when you get in the car.

Decades of research consistently shows us that simple repetition of an action in a consistent context leads, through associative learning, to the action being activated upon subsequent exposure to external cues. I.e it becomes habitative.

Actions become Behaviours become Habits. It will always begin as an individual action. This is a thing we do once, twice or a few times without consistency. They can be considered a behaviour when they are repeated consistently over time.

While the actions require, on a neural level, elements of planning, reasoning and problem solving they will remain an action. It will feel like it takes effort to enact. At this stage motivation is generally high, so the effort required is not a huge barrier at this stage.

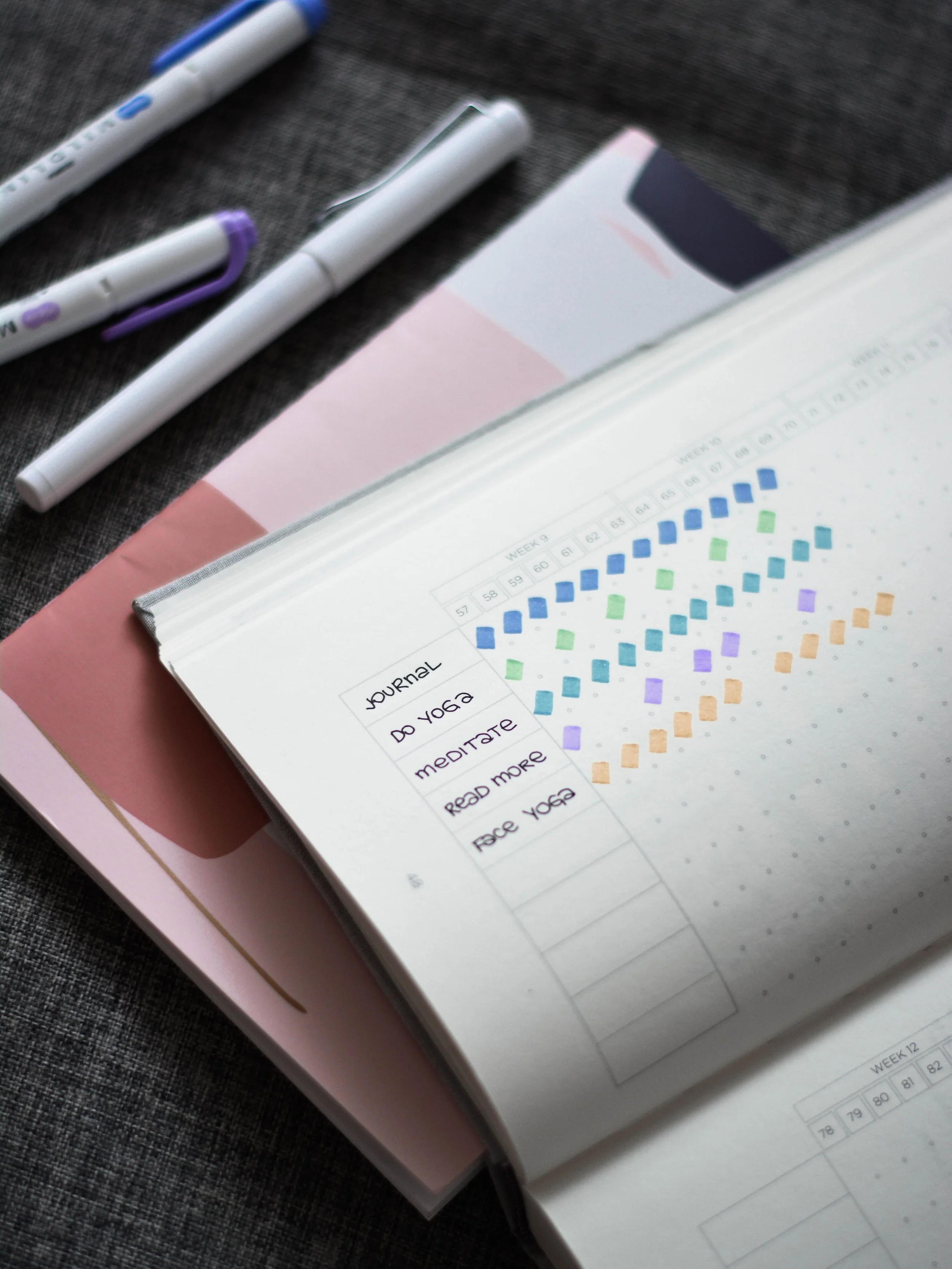

So: behaviours are consistently repeated actions. If you go to the gym three times a week consistently for 6-8 weeks, we could call this an exercise behaviour. If this continues for six months, it is likely an exercise habit.

We literally build habits. With each repetition, neural connections are being made, developed and refined as we literally programme “go to the gym” into the brain. It becomes more automatic (especially when done consistently around other, triggering, actions, such as straight after work). It takes less effort to enact.

Triggering actions, or behavioural prompts are very useful here. These can be doing things order, such as leave work, go gym, or setting a reminder on your phone to hold you to account, or just having a snack mid afternoon, to ensure you have the energy to train later.

Remove the Barriers

In the early stages, it is helpful to make the action as easy to repeat as possible. Think behavioural science over exercise science here. Think: what are the potential barriers? How can I remove or minimise them?

Common barriers include perceived time, money, hassle factor and previous negative experiences. Remember that behaviour form with repetition. NOT going training can also be built as a behaviour! As can sitting on the sofa straight after work and so on.

Other barriers can include an overly complex programme for a beginner, long sessions for someone who is pushed for time or high volume weeks for parents during school holidays. Making the exercise easy to do and repeat is more preferable.

Experts and therapists will often refer to the ABC model:

Antecedents - Behaviour - Consequence

Behaviours are more likely to happen when the consequence is pleasurable. Now, pleasurable is subjective in this context, as what appeals to one may not to another. This means that time should be taken to work out what type, time, duration, intensity, venue and even potentially partners are of preference to the athlete. The programme should then be tailored to these preferences.

Never be tempted to stick to an exercise you or your client doesn’t like, simply because someone told you once that it was superior to the alternative. In the world of health and fitness, there is no such thing as a “must do” exercise.

Exercise only works if you do it consistently and you’ll only do it consistently if you take pleasure from it.

Setting goals can work, but it is preferable that these are process, rather than results, based rather results based in the early stages. “Train three times every week” is much better than “add 30kg to my deadlift” at this stage. Your brain chemistry will reward you every time you achieve this goal, helping to carry on the behaviour.

Conclusion

Ultimately, in order to gain the maximum benefits exercise, exercise behaviours need to built. As we have seen, the process of repetition programmes behaviours into our brain.

If repeated enough, these behaviours become automatic. Athlete preferences, process goals and behavioural prompts/triggers all need to be considered and used.

Some questions to ask, to which the answer should be “yes” to ensure you are on the right track:

Is the exercise planned enjoyable?

Does the time of day and duration suit the athlete?

Has it been scheduled around other activities the athlete currently does and enjoys, to prevent any conflict?

Is the venue easy to get to and nice to be at?

Clearly, taking a behavioural science approach to developing behaviours and habits with regard to exercise is only one part of a much larger whole when it comes to optimising human performance. We spent a lot of time discussing behavioural science alongside other aspects of performance and health psychology in The Adventure Professional programme, more of which will be shared over time.